In her 1970 treatise, On Violence, Hannah Arendt challenges the common political assumption that violence is simply the most extreme manifestation of power. Instead, she argues that “Power and violence are opposites: where one rules absolutely, the other is absent.” And while “Violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it.”

Arendt’s most significant contribution in this work is her redefinition of political terminology. She argues that we often use “power,” “strength,” “force,” and “violence” as synonyms, which leads to a misunderstanding of how governments actually function.

Power: For Arendt, power is never the property of an individual. It belongs to a group and remains in existence only so long as the group keeps together. It is derived from consensus and acting in concert. Even the most totalitarian States, she argues, and the most messianic leaders, are incapable of gaining and exerting power on their own. Adolf Hitler, for example, was not a one-man-band. It wasn’t his grip alone that choked the democracy out of Germany and massacred millions. Nazi Germany, like all totalitarian regimes, had a sophisticated power sharing apparatus. And though it is true that Hitler had a weirdly visceral effect on his followers, his was a power shared with a dedicated base, one that could have been taken away from him from within the power structure if certain conditions arose.

Violence: This is essentially instrumental. It relies on implements (such as weapons) to multiply natural strength. Violence can destroy power, but it can never create it. “Violence appears where power is in jeopardy,” she writers, “but left to its own course it ends in power’s disappearance.” This is because violence is not sustainable long-term. “No government exclusively based on the means of violence has ever existed.” How could it? If it had, who among the nation would survive to tell the tale? And if there are no survivors, then who is there to rule over? And without anyone to rule over, how can there be power. After all, power is, in essence, the dominance of one group of people over another. This dominance, if exerted solely by violent means, will extinguish itself or simply be met continuously with counter-violence (violence begets violence). This is why, for the British Imperialists, hearts and minds was such a big thing. The British knew to use violence sparingly (and it was horrific when they did use it), sincerely recognised its ugliness, and understood its long-term futility. This is where the confused notion of the British Empire being a benign one retains credibility with those who believe it. By being less violent than other Empires (as if being less violent than other violent entities is ok), the British were somehow different in mindset and motivation. Indians, for example, were not seen as equals. Just because they were rarely slaughtered en mass doesn’t change that, nor can such slaughters be blamed on crazed individuals (again, power is exerted as part of a group). That is the ultimate cop-out. In truth, the relative lack of violence practiced by the British, and as was the case with the abolishment of slavery, was a reflection of their belief that such ugliness was beneath them. To be violent, to practice slavery, even, was to behave like a “savage,” unbecoming of civilised people. Violence was to be practised only when necessary, as a last resort, as if punishing a child. Quelling an uprising, for example. Of course, this was all pretence. Whether they believed it or not, the British were not civilised or better than others. But as an Empire, as a supreme power, they understood the futility and unsustainability of violence.

With these considerations in mind, sees violence as being rational only if it pursues short-term, achievable goals. Self-defence, for example. However, because the consequences of violent action are unpredictable, it rarely leads to the intended long-term political change.

Key Arguments:

The Bureaucratic Threat:

Arendt identifies the “rule by Nobody” (bureaucracy) as one of the most potent provocations of violence. When people feel they have no way to argue with or influence their government, they turn to violence as a way to be heard.

The Loss of Authority:

When a government loses its legitimacy (its power), it often compensates by using violence to maintain control. Arendt warns that while violence can sustain a regime, it cannot create the “acting in concert” required for true political stability.

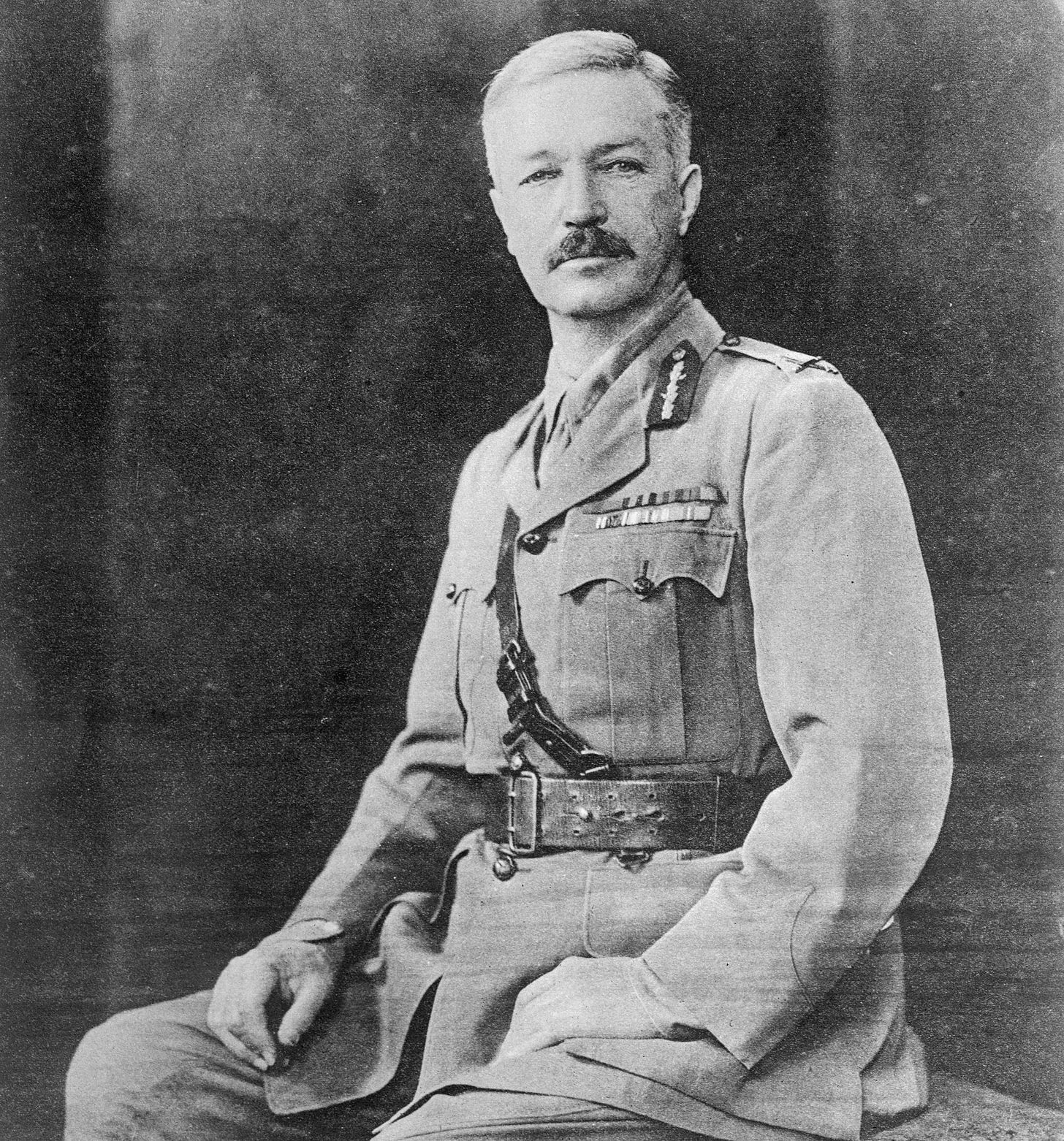

An example of this could be the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre of 1919, an event that proved correct the British view that violence was, ultimately, self-defeating. Acting on the orders of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, British soldiers dealt with a large protest by deliberately concealing exits before opening fire on an unarmed crowd. The rationale for this would proved to be a pathetic as it was evil. Brazenly stating that his aims were not to disperse the protest, “but to punish the Indians for disobedience” (which evokes the general mentality the British had of colonised peoples as being less civilised, in the sense of being “child-like” psychologically, and therefore to be treated as children in most respects), Dyer also openly justified his orders on the basis of saving face. “I think it quite possible,” he said, “that I could have dispersed the crowd without firing but they would have come back again and laughed, and I would have made, what I consider, a fool of myself.”

But saving face could be also be read as fear of losing authority. For Dyer, the protests that day, pre-planned in response to the Rowlatt Act, could, if left to go ahead without reprisal, threaten the lives of British men and women, and even British rule itself. It is ironic, then, that it was the carrying out of his orders that further weakened the legitimacy of the British Raj. And the British establishment knew it. Though, incredibly, no charges were brought against Dyer, he was removed from his rank in disgrace by furious ministers and the like. Even Winston Churchill, all in favour of “using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes” and Secretary of State for War at the time, was appalled, calling the attack “utterly monstrous,” while former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith called it “one of the worst, most dreadful, outrages in the whole of our history.”

But still, the lack of criminal charges tell its own story. The actions carried out, though “utterly monstrous,” were not deemed worthy of imprisonment or, still in effect at the time, court martial and execution, just a forced resignation and public disgrace, as if Dyer had behaved merely improperly or unprofessionally. Despite Churchill’s graphic detailing of the event in a speech to The House of Commons on 8th July 1920, and a near unanimous support of the government against Dyer, he still retained significant support, most notably from the House of Lords, the unelected, upper chamber of Parliament, filled with members of the aristocracy and the most snobbish, unhinged elements of upper-class British society.

Support also came from the poet Rudyard Kipling, who echoed the sentiment that Dyer was preventing a larger uprising and was therefore merely “doing his duty,” while The Morning Post newspaper ran the headline, “The Man who Saved India,” raising £26,000 (about £900,000 in today’s money) as from members of the public, an obscene amount that Britons today should be truly alarmed by. That is a lot of people donating a lot of money.

But it’s not really that surprising, is it. For all its claim of being civilised, of civilising the world, of being benign, fair and good, the British mindset was no different to the one instilled in their offspring in America and the one put into unrestrained practice in future foes, the German Nazis. This mindset was one of a pure belief in the notion of white supremacy. And no matter how averse the upper-echelons of the British ruling classes were to violence, there would always be a loose canon somewhere. Reginald Dyer was one. Consider this attributed quote to get a sense of his air of superiority - “Some Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods. I wanted them to know that a British woman is as sacred as a Hindu god and therefore they have to crawl in front of her, too.”

Such a mentality is incapable of being non-violent and incapable of exerting power, simply because it is built on lies as well as hate. Adherents to such beliefs hold no authority, simply because they are wrong. For Arendt, a lack of authority diminishes power, which leads to outbursts of violence. Violence is practised, therefore, by the weak and desperate.

Biological Justifications:

Arendt also criticises thinkers (like Sorel or Fanon) who justify violence as a “creative” or “life-affirming” force. She argues that viewing political violence as if violence is a natural “cleansing” process as dangerously dehumanising.

Arendt’s central warning is that we should not mistake the efficacy of weapons for the strength of a political body. A government that relies solely on violence is not “powerful, ”it is, again, a regime in a state of collapse, substituting command and obedience for the mutual agreement that constitutes a healthy political body.

So, was Arendt strictly against violence? Reading this text, her position appears to be more nuanced than a simple yes or no. While she is deeply critical of violence and views it as a failure of politics, she is not a total pacifist. She treats violence as a phenomenon that can be justified but never legitimated, making a sharp distinction between these two concepts.

Legitimacy for Arendt comes from the past; it is based on the initial act of people coming together to form a community. Because violence is instrumental and coercive, it can never be legitimate.

Justification relates to the future; it is based on a specific goal. Arendt acknowledges that violence can be justified in cases of immediate self-defence or to right a “crying wrong.” For instance, if you use violence to stop a clear and present atrocity, that act may be justified by the urgency of the situation.

But Arendt is acutely aware that violence is inherently unpredictable. Once a violent act is committed, the “vortex of violence”1 often takes over, leading to consequences that the original actors never intended. She warns that violence is only “rational” when used for very specific, short-term goals, that the more distant the goal (e.g., “world peace” or “a classless society”), the more dangerous and irrational the violence becomes.

She is also against the glorification of violence and its use as a standard political tool. She viewed the 20th-century trend of treating violence as productive or cleansing as a path toward totalitarianism. However, she remained a realist who recognised that in extreme, non-political moments, violence might be the only way to react to an immediate threat - even if that reaction could never build a stable government.

Ann M. Carrington, The Vortex of Violence: Moving Beyond the Cycle and Engaging Clients in Change, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 44, Issue 2, March 2014, Pages 451–468, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs116