The ‘Typical Manc’ and the Cliched City Part One: Joy Division and the 1970s

The first in a series of essays on sense of place, identity, and stereotypes

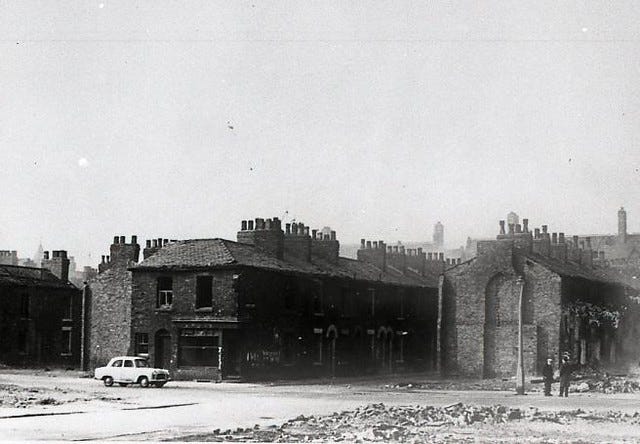

In the latter decades of the twentieth century, the city of Manchester underwent a dramatic transformation. In seemingly perpetual decline, the world’s first industrial city had become a relic-like place, teeming with run-down streets consisting of industrial age housing, its skyline a sprawl of old mills and factories, many of which long abandoned. Beginning in the 1950s and 60s, huge swathes of slum clearances took place, with residents relocated into other areas from dwellings unfit for habitation into new high-rise flats.

Despite the necessity for improved housing (some of which would prove to be just as unfit as the housing it replaced in a mere matter of years, most notably the Hulme Crescents), this mass demolition project had a somewhat unforeseen effect on the identity and sense of belonging instilled into communities over a hundred years or more. The separation inflicted from the clearances led to disbandment, and where once doors were left unlocked, and where everyone knew everyone else, came hives of strangers and vagabonds. Over time, a new breed of Mancunian was born, and new communities, or sub-cultures, emerged from the rubble, bound together by football, music, fashion, and, in later years, the rave scene. All of this, it could be argued, was exacerbated by the Thatcherite implementation of neoliberal economics, and a cultural shift, taking place throughout the UK, that saw new emphasis placed on the individual. This emphasis hinged on the person’s responsibility for their own livelihoods, and also, for the greater economy in the form of privatisation and the encouragement of private enterprise. This responsibility, intertwined with an increasingly rampant consumerism, gave rise to a superficial take on individual expression, which would ultimately take the clone-like behaviour of sub-cultures to new levels. Having a decent life, and being an individual, became reliant on having the best things.

All of this, however, is generalisation. Like with all things, how societies develop, and change is full of nuance and complexity, and although clarity is gained in hindsight, it’s difficult to pinpoint exact moments or events that diverted society into one particular direction. All we can say for sure is that a great change has occurred in the UK during the turn of the millennium, one that has been apparent for some time, but hasn’t had the necessary depth of research required to understand how and why, and what contribution it has had on present-day issues. As identified in some of my other work, a shift in sense of place has occurred that has, for many people and communities, proved to be disorienting and alienating. The ripple effects of this shift have been played out in the early stages of the 21st century, and is now presenting us, in the present, a serious threat to further progression away from old and damaging ideologies. In basic terms, the lurch to the right of our political lines stems directly from en masse sociological change. In retaliation, there is a call for some perceived notion of a past where things were better and simpler. For many people, the world no longer makes sense, and there is a pining for ‘the way things were.’ It is important that we reflect on this, including in our reflections an understanding on what is, essentially, a tribal, us-and-them mentality that exists not just between nations, but between towns, cities, and even between inner-city areas and estates, and in how these mentalities are formed.

Although a shift in sense of place is nationwide phenomena, what makes Manchester such a fascinating case study lies in its ability to succeed in the adaption and implementation of change, something the city has done for over two hundred years. Added to this success is the mythology that surrounds the city, and its iconic status as a hub of cultural and economic activity. In many ways, Manchester has been rendered a cliché, and its citizens almost as caricatures in people’s assumptions of them. These assumptions in themselves are evidence of Manchester’s appeal, and of its importance in the creation of the modern world, something which will be looked at in the following weeks. The purpose of this essay, however, is to explore the promotion of a somewhat unique kind of archetype - matched only in commonality with the widespread perceptions of scousers and cockneys - that is a manifestation of the new Manchester.

To begin at the beginning – in bleaker times

As the 1970s drew to a close, a depressed and defeated mood had long since descended on Manchester. Mancunians, long known for their ‘northern grit’ and work ethic (celebrated in the city’s adopted symbolism of the worker bee), became known for being miserable. Miserable people from a ‘dirty old town’. When you hear people talk of Manchester during that time, both Mancunians and outsiders who either worked or studied in the city, the words ‘grim’ and ‘mundane’ are frequently used.

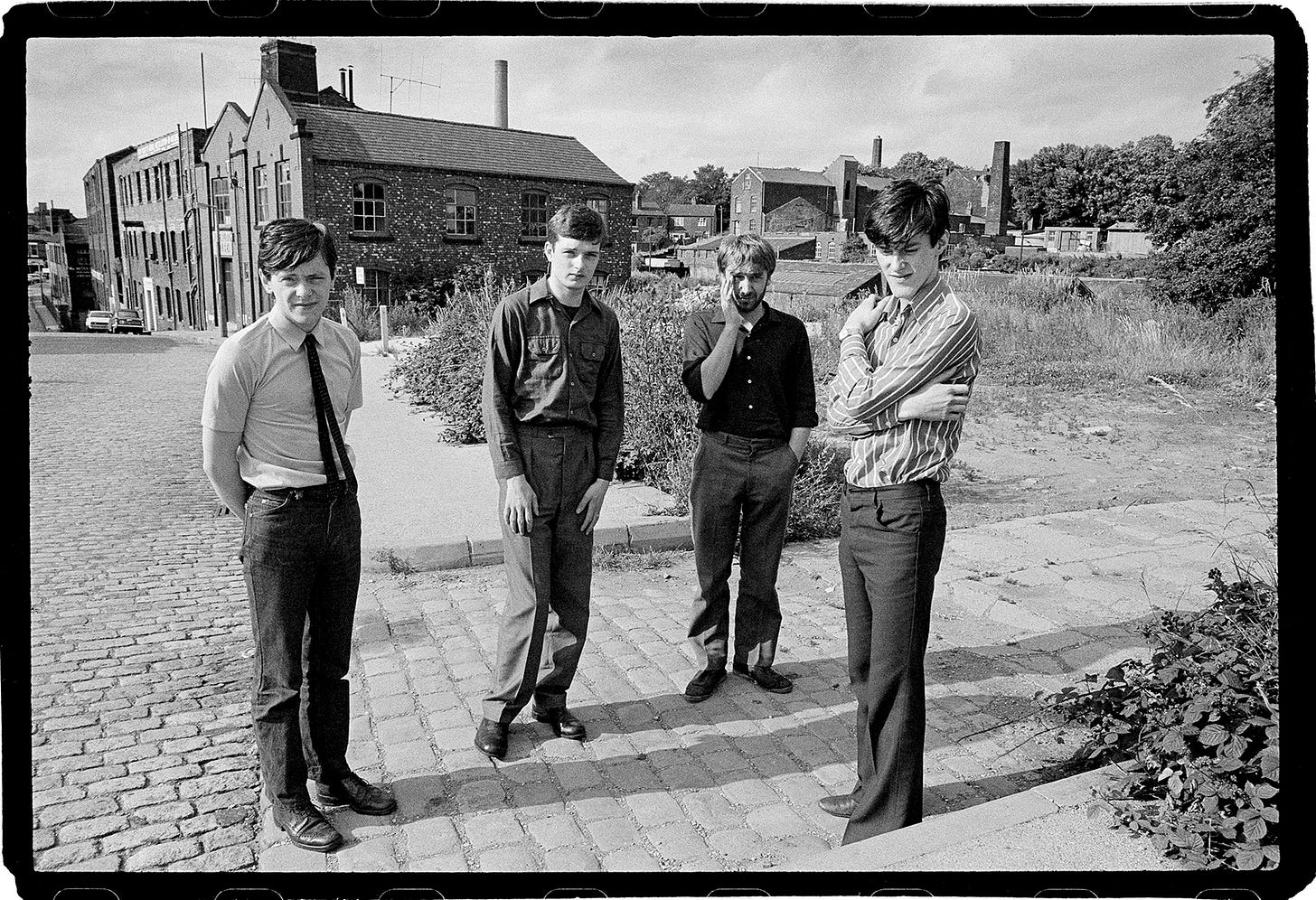

Undoubtedly the most iconic cultural depiction of that Manchester is in the music of Joy Division, whose sound is perceived as having captured the “Mancunian urbanism” in compositions that conjured a vivid “mindscape” of post-industrial decay and ruin. This is unsurprising, as with the city itself everything about Joy Division was devoid of the flamboyance and (the actual) joy found elsewhere. It was hardly disco. Through the lyrics and baritone of Ian Curtis, Peter Hook’s distinctive bass, Bernard Sumner’s haunting guitar riffs, Stephen Morris’ machine-like drums, and Martin Hannett’s sci-fi-like production, the band resonated with Mancunian listeners who heard in the music a somewhat cinematic reflection of the city’s then current state. Much has been written on these conjurations by music journalists and people, like Tony Wilson, who promoted and eulogised the band.

But is the idea of Joy Division being a distinctively Mancunian band true? Maybe a much broader question would be better. Is any music distinctive to one particular place? Are The Beatles distinctively Liverpudlian? Are Nirvana distinctive of Seattle? The effect and meaning of music is subjective to the listener, akin to the literary notion conceived by Roland Barthes, that of The Death of the Author. This question is expanded on and examined brilliantly by Leonard Nevarez in his article for the Journal of Popular Music Studies, entitled How Joy Division Came to Sound Like Manchester: Myth and Ways of Listening in the Neoliberal City (see link below for a highly recommended read on the topic).

This poses a further question, one that is tied in with the effect of place on the human psyche. As Nevarez correctly points out, there is scant evidence to suggest that the members of Joy Division had any overt notions to champion a Mancunian image or identity, or of having any aims to associate themselves with Mancunian imagery or locations. There are no images of specific locations in any record covers or sleeves, and no mention in the lyrics of Curtis “explicitly” referencing “Manchester’s specific landmarks or neighbourhoods,” or of any “concrete reference to Mancunian life” (Nevarez. L.) Another point to make on Curtis, and with drummer Stephen Morris, is the fact they were raised in Macclesfield, a small market town bordering Greater Manchester, Derbyshire, and Staffordshire, which poses yet another question - to what extent are Curtis and Morris even Mancunian? - an important question considering the idea of the band as having a distinctively Mancunian sound, of which Curtis’ lyrics are a crucial component.

In relation to Curtis’ lyrics, his exposure to the Mancunian landscape of decay and ruin was likely minimal. It’s impact on his writing, then, is surely debatable? Of course, Macclesfield would have had its fair share of post-industrial decay, but it wasn’t on the scale to that of Manchester. Also, when we listen to Curtis’ words, we predominantly hear a more personal anguish. And although this is, no doubt, tied into his environment, the existential quality to the words point to Curtis being preoccupied with something bigger than just Manchester, if the city even had any bearing at all.

This all leaves interesting considerations, then. Was the Joy Division sound a reflection of the bands’ view of their environment, or the direct but sub-conscious effect of their environment on them, not just as individuals, but as a collective? Was the bands’ sound and image, the way they presented themselves, a nod to their environments in any way at all? Much of the bands’ paraphernalia, for example, is made up of niche and abstract things, as demonstrated on their album covers (both of which were designed by Mancunian graphic designer Peter Saville). Even their band names (they were originally called Warsaw), speak to something darker than post-industrial decay (the name Joy Division actually comes from the 1955 novel House of Dolls, and a reference to a sexual slavery wing of a Nazi concentration camp).

I would argue the former. Believing that people are, though not absolute, products of their environments, then their environments must play a key role in any artistic expression. I say not absolute as, in the words of James Joyce, when explaining why he focuses his work on Dublin, “In the particular is contained the universal.” The impact of environment, or place, however, has the simultaneous quality of being superficial whilst being authentic. By this I mean it is almost inescapable, yet is only something that exists at surface level, seen primarily through accents and dialects, for example. It doesn’t penetrate through to the actual human being. So, even though I am a Mancunian, that is only by place of birth. It is a social construct, in a way, but one not by design but in something bordering the intrinsic, a development of complexity and nuance difficult to comprehend.

If we think of the contributing factors in our developments, we think about school or knocking about with mates on the streets. We think about the daily interactions in all the places we have been, and of the scenery and our surroundings, the effect they will have on mood, and mental state. But also, we think about the history that surrounds place, those moments and events that shape community spirit and identity, that become passed down through generations. Think of that ‘northern grit’ and work ethic associated with Mancunians, which in some abstract way forms stereotypical perceptions of Mancunians that become widespread not only outside the city, but within.

Of course, these perceptions are just that. They are illusions, ultimately, a creation of circumstance. Manchester was the heart of the Industrial Revolution, but the workers that ran the machine were from all over England and, even more so, from Ireland.

The contribution of the mass migration of Irish people to cities like Liverpool and Manchester cannot be overstated and is one that will require much more reflection (though plenty of work will exist). The point to make here is in the creation of the Mancunian ‘worker bee’ image. If many of the workers in Industrial Manchester, and within many of the cities most deprived areas (which at that time was truly horrific), were either Irish migrants or their descendants, then what contribution would that have had in the formation of a Mancunian image? Basically, the idea of Mancunians as hard workers does not come from primarily Mancunian people i.e. people with a long lineage tied to Manchester and its surrounding areas (Salford, or even Lancashire as a whole).

In his book Mancunians: Where Do We Start, Where Do I Begin, David Scott refers to Manchester, and Mancunians, as “mosaic” (Scott. D. 2023). Scott, correctly, identifies the contribution of people from various background, nationality, and culture, to Manchester’s success (as a capitalist economy, mind), and in the construction of the ‘typical Manc’. Indeed, from its inception as industrial powerhouse, and ever since, mass migration to Manchester, not just from abroad but within England itself, has been a constant occurrence. In 2025, if I went into any building in Manchester, including its inner-city areas, and opened a window to throw a stone, the chances are it would reach someone from a different cultural background, who would speak any one of up to 200 languages. Another stone would reach someone from another cultural background, and so on. The point being, that what is defined as a ‘typical Manc’, or someone with ‘northern grit’, is, predominantly, an image of a white, Lancastrian sounding man. This, in some ways, could also be a contributing factor in the formation of the modern ‘typical Manc’ archetype, with the divergence away from this image to the one of a cocky, swaggering, Liam Gallagher-esque type, spectacularly referred to by Scott as a “Mancinstein.” This is something that will be looked at in the next essay.

Returning, however, back to the 70s, and of Joy Division as the enduring image of Manchester in that period, we must conclude, based on the evidence provided, and of Joy Division’s actual popularity at the time (they were very much a low-key band with limited air time on mainstream radio and on television, which consisted of only three channels back then), that it is a posthumous notion, something formed in the cultural consciousness after the event, aided by recollections of music journalists and proponents of the band. Furthermore, the notion is a somewhat hauntological one. There is a visceral sense of a lost future around Joy Division, predicated on the untimely death of Ian Curtis. But it also the fact that they were not, at the time, a famous band, that feeds into this hauntological aura that now surrounds them. Considering the band’s greatness, and they were a great band, and the originality of their sound, combined with the success of New Order, the bands reincarnation after Curtis’ death, then we can safely assume that the fame wouldn’t have been too far away. We will never know, of course, what direction the band would have taken if Curtis had survived, if the band would continue to reflect Manchester in the city’s own reincarnation, or remain one based on a predominant mood of existential anxiety.

What we do know, is that Joy Division, as a sound and an idea, have become ingrained into the cultural fabric of Manchester, inseparable from the post-industrial landscape, and the sheer dreariness of the city in the 70s. What should also be mentioned, in relation to Curtis specifically, is that the existential dread in his words could speak of 70s Manchester itself. The sound the bands’ musicians created around those words, reflected the city’s look at that time. Decay, ruin, rubble, abandoned buildings, boarded up houses, high-rises, in short, death. Curtis’ existential themes, his somewhat morbid fascination with death or morbid themes, similar to that of the poet Sylvia Plath, reflect Manchester’s state at that time.

Furthermore, there is the surrounding geography of Manchester, the encirclement of vast hills that overlap and stretch endlessly in the distance, summarised viscerally by Paul Morley:

“There was the Manchester damp and the shadows and omens called into dread being by the hills and moors that lurked at the edge of their vision. It wasn’t soft, where they lived. It was stained green and unpleasant. It seemed to be at the edge of the world.” (Nevarez. L. 2011.)

But as Nevarez points out in his counterargument, none of this explains the bands appeal with people outside Manchester or the north of England. It certainly doesn’t explain the bands appeal to people of middle-class backgrounds, from well-to-do areas. For these people, Joy Division will provide a different experience, one still tied in with existentialism, but without the conjuration of post-industrial imagery or experience.

To conclude that Joy Division are not a quintessential Mancunian band, or the sound of Manchester in the 70s, is difficult. Despite Curtis’ and Morris’ upbringings on the city’s doorstep, the sound of Sumner and Hook tap into the environment they were raised in. If we ask ourselves a broad, hypothetical question – what kind of music would Sumner and Hook have produced if they came of age in any other decade? – we can pretty much guarantee that it would have been, perhaps, of a different tone. We can, as further evidence, point to New Order, who were, from the second album onwards, a much more upbeat band, who forged a separate identity from that of Joy Division, and became reflective of the more relaxed, for lack of a better word, period of the late 80s and early 90s.

Environment, then, is a major factor in a person’s development, thus feeding into constructed notions of stereotypes and archetypes. All these things shape our existence, and of the lives we lead. ‘You can take the boy out of the street, but you can’t take the street out of the boy’, and similar maxims speak of our awareness of the innate quality our environments have on us, ones we can’t escape from, even after we have long left behind the place we came of age in.

In his poem The City, C.F. Cavafy writes:

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighbourhoods, turn grey in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city.

Cavafy is not being literal. He is speaking metaphorically, that no matter where we go, what we do, the place we came from will always be with us, and the labels associated with a particular place carried with us.

In the next essay in this series, I will look to the 80s, Manchester’s re-birth from post-industrial collapse into a neoliberal, consumer-based model, and how the ‘typical Manc’ archetype began to form.

References

Nevarez. L. Journal of Popular Music Studies

Scott, D. (2023). Mancunians: Where do we start, where do I begin?. In Mancunians. Manchester University Press.

Recommended Reading

https://hakka3.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/nevarez-how-joy-division-came-to-sound-like-manchester.pdf