Union Jack’s and St. George’s flags have been popping up on lampposts everywhere over the last month. Where I live, a “team” of lads, going by the It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia-esque Flagman, have been getting about decorating the local areas in the style of 1950’s street parties, as if re-enacting the celebrations had for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Facebook groups from areas all over the country have been sharing similar stories, with videos of roundabouts being sprayed with the St. George’s Cross, all of which confirmed by local and national media. Comment sections are full of jingoistic joie de vivre, if I can use a foreign phrase, celebrating the colour (one is a white flag with nothing but a red cross on it, by the way), and the sense of meaning, community, and togetherness the flags give them.

For these people, the flags are harmless expressions of pride, something that is the norm in many countries, whereas for others, they are symbols of exclusion and aggression. But beyond the culture war surface, their appearance provokes a critical question: what does it mean to be British today, and why does that meaning remain so stubbornly tied to denial, nostalgia, and myth?

Shared between nations, divided by class, and shadowed by a colonial history that simply isn’t there for a great many people - colonial amnesia, if you will – Britishness has become ambiguous, open to interpretation, its meaning dependant on which part of Britain you are in, and which kind of person you ask. It is also entirely hauntological, being so deeply entwined with the past. The return of the flags is symbolic of this, and is, in essence, an attempt to stabilise a national identity that feels increasingly unstable.

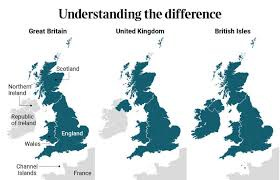

This instability is, to my mind, a fallout from the collapse of Empire, empirical collapse not just being consequential for the colonies. Collapse of empire is also the collapse of narrative and understanding that informs identity. Though it affects many people across Britain and Northern Ireland, it is most acute in the English. Englishness is the toxic ingredient here, with Englishness being the dominant strand of Britishness. If this is confusing, by the way, for anyone who is not familiar with Britain or the UK, it will become clearer throughout.

I acknowledge that this labelling of Englishness as ‘toxic’ risks rubbing people up the wrong way. English people, specifically white male English people, are a sensitive bunch right now. With this in mind, I’ll clarify my position – on the pieces of land known by humans as the British Isles, policies and decision-making are predominantly English-centric. The UK, that important distinction I will get round to, is by design an imperial construct. This is a key factor in any understanding of Britishness and British history. And while English nationalism cloaks itself in the Union Jack AND the flag of St. George, the other members of the Union are marginalised voices. The Union Jack, in this sense, could be said to be a disguise.

Finally, before I really get into this, I’m not saying that there are no problems within the Scottish, Welsh, or Northern Irish entities. Many people in these countries, as demonstrated by the Brexit vote and the success of Reform UK, are just as susceptible to the new brand of nationalism that has arisen. Somewhat paradoxically, however, and to add to the confusion, these countries have their own brand of nationalists that are equally as harmful, and delusional, as any English ones.

I am, just so you know where I’m coming from, a naïve soul. I believe in a crazy notion of a borderless world. Nationalism is nationalism no matter who is practising it. When people on the left sympathise with the SNP or Plaid Cymru, for example, I get a little jittery, despite understanding their fundamental gripe. I could be wrong on this, but I just want to put it out there, as it automatically qualifies me as a Unionist. But I am my own brand of Unionist. I’m anti-monarchy, I’m against Parliament being based in one location, and think it’s stupid to have three countries on a tiny piece of earth where cultural differences are minimal. But again, I’m very naïve. I know I’m naïve. That’s why I don’t waste my time promoting the borderless world ideal.

The British Psyche

Many people don’t realise how complex the British psyche is. It is a mosaic of cultures, status (class), and ethnicity (especially if you see Welsh, Scottish, Irish, and English as being different ethnic groups, as some do).

Many factors need to be considered. Whilst it is very easy to judge this confusion as being borne out of delusion, ignorance, or plain stupidity (I’m not including the racists just now, as I’m focusing primarily on everyday people who are not racist, but who believe in Britain as an overall force for good), the answer requires a lot more nuanced thinking, and broader understanding.

While England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are formally united, they are also distinctive nations with their own histories of domination and resistance. Even within England, regional divisions such as the north/south divide, rural and urban divisions, and divisions between the middle and working class, make “Britishness” an unstable category, and “Englishness” an uncomfortable burden. Yet it is precisely this instability that transforms a flag into a metaphorical comfort blanket.

Whilst many feel an attachment to the Union Jack, there are equal attachments to flags of each individual nation. Where things get complicated is in the awareness of imperial dominance. There is a fundamental resentment at the edges of the Union, and confusion at its centre. The result is a psyche that is internally fractured, unable to tell a coherent story about itself, and thus prone to nostalgia for a simpler, more triumphant past.

For many white English people (and other people within the UK as well, though the English are by far the main culprits) charges of colonialism and genocide are genuinely bewildering. They simply don’t get it - passing it off as being in the past, of a time, and not the fault of those alive today.

Colonial Amnesia and the Bewildered Majority

This colonial amnesia is one of the most striking features of contemporary Britishness. There are many, many reasons for this, and I can’t focus on all of them here. Instead, I can attempt to summarise, seeing the phenomena as a consequence of cultural and systemic suppression and denial, and good old fashioned historical revisionism. As the saying goes, he who wins the war writes the history. Or something like that.

The suppression is not necessarily always a conscious one. It could be that the truth is too much to handle for some who are deeply attached to the perception of Britain, or England, that exists in their heads. This is actually quite natural, as we all have a sense of place. Places have meanings, and those meanings are based on our experiences and our understanding of them. The reason why England can be seen as a quaint, polite, orderly place, or something out of Enid Blyton, is because for a lot of people it is, or was. The same is true for those who see, or have seen, England as a grim, miserable little place, dominated by grey skies, tower blocks, and urban decay. There is a truth to both of these perceptions.

If your attachment is based on a positive version akin to merry old England, for example, then stories of genocide from, say, India, won’t make much sense. How could such a thing be? How could our lads do that? It must be the fault of those we were trying to help (the ungrateful savage, too primitive to know that the benign Empire was “civilising” them).

Denial and revisionism such as this is a lot less complicated to understand than unconscious suppression. Typical soundbites of those in denial include That’s all in the past. Didn’t we abolish slavery? Didn’t we build railways and schools? For them, Britain’s global history is framed as a tale of progress and civilisation, not plunder and subjugation.

Whether it is denial or ignorance, it is ultimately the outcome of a long cultural process. The British education system has largely sanitised empire, presenting it as a mixed but overall positive inheritance. Media and political discourse reinforce this selective memory, celebrating Churchill, for example, as the defender of freedom while muting the Bengal famine, the Mau Mau camps, or the brutalities in Ireland.

For those descended from colonised peoples, empire is a living memory, inscribed in family histories and cultural identities. For the majority of white Britons, it is distant background noise. The confrontation with empire thus feels alien, even accusatory: not only a challenge to the nation’s past but to their own inherited sense of self. The denial functions as an existential shield. To accept the truth would be to destabilise identity itself.

Class, Alienation, and the Inheritance of Suffering

Yet colonial amnesia alone cannot explain the complexities of British nationalism. Class remains central. The empire was not only a system of global domination but also a structure of hierarchy at home. The ruling classes who governed colonies also exploited the labouring poor in Britain’s factories, mines, and workhouses. The industrial revolution was powered not only by the profits of empire but by the exhaustion of working-class bodies, subjected to inhumane working conditions. Many of these bodies were children.

This shared but unequal suffering complicates narratives of privilege. While racialised minorities face structural exclusion in Britain, many working-class whites feel their own lives are marked by precarity, judgment, and disdain. To them, discussions of “white privilege” feel like erasure of their own struggles, another form of silencing by elites who neither represent them nor respect them.

This is the terrain on which nationalism thrives. Alienated from wealth and power, many working-class whites also feel alienated from discourses of anti-racism that they perceive as hostile to their lived experience. They are caught in a double exclusion: scapegoated by the powerful and estranged from the language of critique. Reform UK positions itself precisely here, offering nationalism as a simple, consoling identity in place of complexity.

The Language Problem: White Privilege and Its Discontents

This term, “white privilege”, crystallises the problem. Analytically, it points to structural realities: white people in the West are less likely to be discriminated against, criminalised, or held back because of skin colour. Yet the word “privilege” is rhetorically clumsy. For those at the sharp end of class inequality, “privilege” feels misplaced. A person struggling to feed their family on a zero-hour contracts could hear the term not as an analysis but as an accusation.

The existential failure here is linguistic. A term intended to clarify ends up dividing. Instead of opening dialogue, it entrenches resentment. In this sense, “white privilege” mirrors the broader failures of British political discourse: words are weaponised rather than shared, identities are policed rather than explored. Nationalism thrives in this vacuum, offering the illusion of plain-speaking truth against the complexities of critique. In short, it is a poor choice of words, over-complicating an issue that isn’t that complicated.

Despite being a response borne out of the very ignorance in which terms like ‘white privilege’ seek to challenge, ‘white privilege’, as a concept, is one of many contributing factors to the current mood in which the raising of flags is allowed. It is, in effect, the continuation of a long-running cycle.

Nationalism as Ontological Therapy

Possibly the most alluring component of nationalism is the promise of security through belonging. Nationalism offers a story of continuity where the reality is fracture, decline, and uncertainty. In this sense, it is hauntological: it longs for a future that looks like a past that may or may not have really existed. It is a politics of ghosts. Reform UK has understood this. Its message is not merely political but existential: Britain must “take back control”. not only of its borders but of its very sense of self. “I just want my country back.”

Existentially speaking, there is also a need for a simpler, yet universal understanding. Nothing lasts forever. This is a rule applied to everyone and everything. Nationalists, patriots (all one and the same) could well do with being reminded of this. England will not last forever. Great Britain, as the name for a piece of land, will one day be renamed or have no name at all. This matters.

Being attached to one place, or one nation/nationality, is to alienate oneself from everything else – other human beings, nature, the universe itself. If Britain is changing, then it is because it is always naturally changing. You can attempt to stop the change through force all you want, but you will only be delaying the inevitable. It simply cannot be stopped.

The irony here is that once something like sense of place is gone it is gone forever. There is no reclaiming it. The people who “just” want their country back will not, in the event of mass deportations and a Reform win in the next election, actually get their country back, as the country they want is nothing but a country that was, comprising of all the nostalgic misremembrances and historical inaccuracies that exist in memory.

In reality, then, that country they want is not the country that was, and you could easily make a compelling argument that says the country we now have is because of the country that was. Mass immigration, explosions in crime, social decay – anything you want – could only come to pass because the conditions were ripe enough for these things to come to pass.

A final truth – the sight of flags on lampposts is not normal for England, at least in Manchester. I can’t speak for any other part of the UK, as I’ve never lived anywhere else. Born in 1984, I’ve only ever known a multi-cultural society, with Manchester being one of the most multi-cultural places in Europe, with over 200 languages spoken at any one time. I’ve only ever had positive experiences of multi-culturalism. Though I’ve had a few disparaging “white boy” kind of insults thrown at me in High School, I’ve always been, I’d like to think, cultured enough and thick-skinned enough, to look at things through, to my mind, their proper context.

St. George’s flags have primarily been reserved for international football tournaments. World Cups and European Championships. Union Jacks are always out for the Olympics, or whenever the Royals decide to inflict a family event upon us. Nobody is arsed about this. Nobody cares. The so-called suppression of Englishness is an imaginary one at best, a constructed one at worse. At its heart is a deeply profound sense of loss, and an acute lack of understanding of when and how this loss occurred. This is where the anti-capitalist left has many answers. But we don’t have all the answers. And this is the difficulty.

Comparisons to 19th and 20th century events can be helpful, but only as a guide. Reform UK, even the EDL, are not literal Nazis. True, they can best be described as Fascists. But this brand of fascism, if fascism is the correct terminology, is something new. It is fascism refracted through both imperial and neoliberal collapse. These are two distinct occurrences that have overlapped to produce a confused and contradictory state of mind, where capitalism is simultaneously the solution and the cause, where the State is both protector and oppressor, where being free means nothing more than having the decency to endure the tyranny of wage labour.

There is, critically, nothing imperial about this new fascism. No desire to conquer, no vision of an expanded lebensraum. It is not outward-facing at all. This is a fascism that just wants to be left alone, to nurse its sense of wounded pride behind the walls of a bloated island. The story it tells is simple: the British, abandoned and betrayed, can thrive on their own. Yet within this story is a void. There is no recognition of the source of Britain’s historic wealth, no acknowledgment that even our relative comfort was built on global exploitation. Without that admission, the imagined self-sufficiency is delusional.

In short: it is fascism without the utopian horizon, stripped of mythic grandeur and reduced to paranoia. An uneducated, nostalgic, nihilistic management of decline and loss, an ideology of survival without future, clinging to flags as talismans against a world it neither understands nor wishes to understand.

This was a great one Craig. As an outsider living on this strange island, it is odd to notice how unaware a lot of British people are of their own country's history (yet mention Congo every time I say I am from Belgium)

Interesting read. There are many places in the essay that I see mirrored here in the States. Perhaps this is a result of changes taking place in neoliberalism. (At least as I understand the arguments made by Byung-Chul Han.) Perhaps each person needs to decide what being "X" is for themself, and less concerned about the views of others. Maybe, one day, people much smarter than me will figure out a better way.